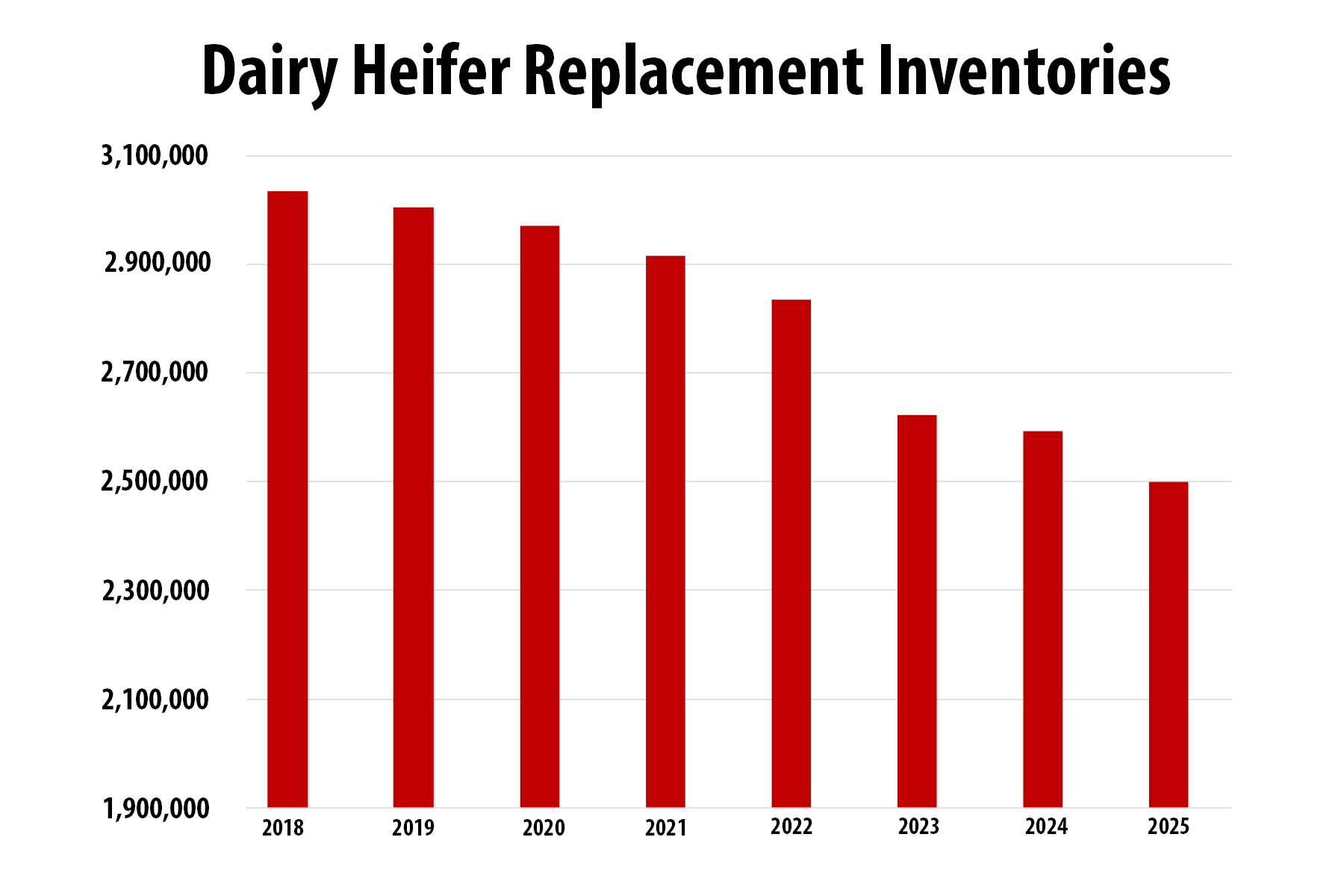

The dairy heifer replacement inventory continues to drop. In fact, it’s the lowest we’ve seen in the USDA’s 22 years of projection.¹ To help balance the low heifer inventory, you focus on breeding long-lasting profitable cows, built from an elite heifer crop. While selecting sires based on the Herd Health Profit Dollars® (HHP$®) index gets you started down the path of creating healthy, profitable cows that last, you can’t stop there.

As soon as that heifer hits the ground, you make sure to give her all the support she needs. You feed high quality colostrum, provide nutritional supplements that support the early development of her digestive system, and follow comprehensive vaccination protocols that strengthen her immune system. These steps bring us closer to ensuring longevity and the future is looking better for our heifer.

In order for this heifer to achieve her highest levels of success, you need to take extra steps to remove as many barriers as possible. Pathogens are lurking around every corner, waiting to ‘pounce’ on the unsuspecting heifer on her way to being your shining star. Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus (BVD) can infect the heifer in utero, allowing her to spread the virus for the rest of her life. Johne’s disease easily infects our youngest animals through exposure to contaminated manure or colostrum. Bovine Leukemia Virus (BLV) can be contracted at any age through blood transmission, leading to lifelong infection. Contagious mastitis pathogens such as Staph aureus or Mycoplasma bovis spread easily in the milking parlor and can lead to her removal from the milking herd almost as quickly as she enters. To set her up for her best chance at success, a screening protocol for various diseases should also be on your to-do list.

Contrary to the implications of its name, diarrhea is actually one of the less common symptoms of infections with this virus. When cattle are infected, they most often experience respiratory illness, if they show any signs of infection at all. Another common symptom of BVD infections is pregnancy loss. You put a lot of work into creating each pregnancy in hopes that the calf will become part of our heifer inventory, so you want to make sure that pregnancy makes it to term.¹

Vaccination programs often include protection against BVD, but that protection is not 100% guaranteed. If a cow becomes infected with BVD while pregnant, maintaining the pregnancy doesn’t mean you’re in the clear. If she was exposed to the virus at just the right time in fetal development, she becomes persistently infected (PI). This means when she is born, she will already be infected with BVD, will remain that way her entire life, and will shed massive amounts of virus to the rest of the heifers around her. What makes this disease even more challenging is that only half of the calves born as PIs could be considered “poor doers” while the other half will appear perfectly normal, even making it to adulthood. Now our high value heifer calf is our very own Typhoid Mary.

Dairy herds across the U.S. are all too familiar with Johne’s. The tell-tale signs, like liquid diarrhea and emaciated cows, are unmistakable to anyone in the industry. But the part you can’t see with the naked eye is the real problem. The seemingly healthy cow spreading large quantities of Mycobacterium avium subsp. Paratuberculosis (MAP) in every ounce of manure she passes. Our brand-new high-value heifer calf ingests MAP contaminated manure within her first few hours of life because she stumbles into a fresh pile while she learns how to use her wobbly legs. She has no idea she just sealed her fate in that moment, and neither do you.

In the first stage of the disease, our infected heifer will show no clinical signs and will not shed the MAP bacteria. This stage² progresses slowly over many months or even years. Our bright young heifer likely has begun her first lactation by the time she moves into stage two, where she begins to shed the bacteria, but you still won’t be able to tell by looking at her. Stage three comes when you can finally see the clinical signs of her disease. With current heifer inventories, the goal for cows remaining in the herd is at least 3.7 lactations.¹ The slow progression from stages two to three allows our infected herd members to potentially shed bacteria and contaminate environments for multiple years.

The challenges keep coming for our heifer as she navigates adulthood. The impacts of leukosis infections are difficult to measure because they touch every aspect of the dairy. This virus can negatively affect milk production, reproduction, and immune function, among other things. The most difficult to quantify economically is immune function. Heifer inventory dictates you should maintain a cull rate under 26.7%,¹ so you work with your veterinarian to create a comprehensive vaccine protocol for optimal health and performance. But some of the cows you vaccinate have compromised immune systems and don’t mount the proper immune response. Epidemiological studies suggest it could be 23% – 47% of your herd.³ Now these cows are left to battle infectious diseases without a full arsenal, eventually succumbing to infection. This is why often, cows infected with leukosis leave the herd for some other reason, such as mastitis or respiratory disease. Because of the virus you couldn’t see, her immune system was defeated by the more “visible” infections.

Like the diseases mentioned above, Staph aureus and Mycoplasma bovis pathogens are typically reason enough for a cow to be removed from a herd as treatment is most often unsuccessful. These bugs are categorized as contagious because of their ability to easily spread from cow to cow in the milking parlor. Just imagine all the effort you’ve put into raising a healthy heifer, only for her to pick up Staph aureus from the cow milked just before her in the same stall.

What can be done?

The best chance of success in avoiding all of these ailments is by reducing risk of exposure throughout her life. A common thread you may have noticed is the inability to see infected animals before it’s too late. Testing calves at birth for BVD with PCR on an ear notch sample prevents PI calves from spreading the virus to the rest of the herd. ELISA testing all cows at freshening or dry off ensures everyone is screened annually for Johne’s and leukosis. Using milk samples, even DHI samples, to screen for contagious Mastitis with PCR can catch pathogens early and reduce spread. Identifying and removing infected cows from the herd reduces the contamination of the dairy environment, reduces risk of exposure, and protects the future of the herd.

Author: Michelle Kaufmann, CentralStar Customer Solutions Advisor

Sources:

¹ USDA, Jan 31, 2025

² https://bi-animalhealth.com/cattle/initiatives/bvdvtracker

³ https://johnes.org/

⁴ https://www.canr.msu.edu/blv/basics/prevalence